Information engineering

Documentation, backgrounders and tutorial material related to information design, engineering, semantics, ontologies, and vocabularies

→ Standards and namespaces

→ Controlled vocabularies

→ Semantic Web Tools

→ Learning resources

Linked Data APIs: theory and practice

Contents of this page

Purpose

- Introduce Linked Data concepts

- Introduce Linked Data APIs

- Understand Linked Data API implementations and different implementation styles (via links and examples)

- Use python to interact with Linked Data Systems

- Understand how to deploy a Linked Data API implementation using pyldapi v3

Theory

This section outlines theoretical aspects of Linked Data API design, rationale and related background.

Linked Data

The term Linked Data refers to a set of practices for publishing structured data on the Web. These principles were described by Tim Berners-Lee in the design issue note Linked Data. The principles are:

- Use URIs as names (identifiers) for everything

- Make these HTTP URIs so that people can look them up.

- When someone looks up a URI, provide useful information.

- Include links to other things, using their URIs, so that readers can discover more things.

The idea behind these principles is on the one hand side, to use standards for the representation and the access to data on the Web. On the other hand, the principles propagate to set hyperlinks between data from different sources. These hyperlinks connect all Linked Data into a single global data graph, similar as the hyperlinks on the classic Web connect all HTML documents into a single global information space. Thus, LinkedData is to spreadsheets and databases what the Web of hypertext documents is to word processor files. The Linked Open Data cloud diagramms give an overview of the linked data sets that are available on the Web.

Linked Data is a way of publishing and interlinking structured data on the web. Resources, and links between resources, can be described in machine readable syntax together with human labels. Most often this relies on the ‘semantic web’ technology stack, with data structured using RDF, and links encoded as HTTP URIs. This allows both human-readable and machine-readable content/interaction to access data resources and their descriptive metadata simply by dereferencing HTTP URIs.

Elements of RDF

Links to the basic references are given in W3C semantics stack - references.

RDF Statements or Triples

The Resource Description Framework (RDF) is a W3C standard (Hayes and Patel-Schneider 2014). Information elements consist of RDF statements. An RDF statement consist of three parts: Subject, Predicate, and Object. This is called a triple.

Identifiers are a key building block of RDF and Uniform Resource Identifiers (URIs) are used to identify a resource.

URIs can appear in each part of a triple, i.e. Subject, Predicate, Object. Where an Object is a URI, this may also be a subject for another statement. Literals are another key part of RDF and are used to capture basic values other than a URI. e.g. strings such as “Gerald”, dates such as “1 April 2019”, and numbers such as “4897”. Literals are associated with a datatype so that it can be parsed. Literals may only appear in the object part of a RDF statement.

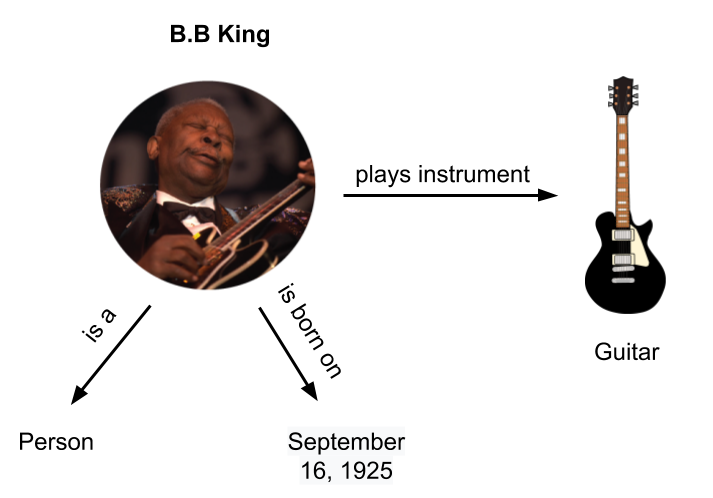

A set of RDF statements is collected together in an RDF Graph. Figure 1 below show an example of an RDF graph encoding information about the singer B.B. King.

Pseudo-RDF triples

<B.B. King> <is a> <person> .

<B.B. King> <is born on> <the 16th of September 1925> .

<B.B. King> <plays instrument> <guitar> .

Valid RDF graph expressed via the Turtle serialisation

@prefix : <http://example.org/> .

@prefix foaf: <http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/> .

@prefix rdf: <http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#> .

@prefix xsd: <http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema#> .

:BBKing a foaf:Person ;

:is_born_on "1925-09-16"^^xsd:date ;

:plays_instrument :Guitar

.

Equivalent RDF/XML serialisation

<rdf:RDF

xmlns:rdf="http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#"

xmlns:ex="http://example.org/"

xmlns:foaf="http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/"

xmlns:xsd="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema#" >

<rdf:Description rdf:about="http://example.org/BBKing">

<plays_instrument rdf:resource="http://example.org/Guitar"/>

<is_born_on rdf:datatype="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema#date">1925-09-16</is_born_on>

<rdf:type rdf:resource="http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/Person"/>

</rdf:Description>

</rdf:RDF>

Equivalent JSON-LD serialization

{

"@id": "http://example.org/BBKing",

"@type": "http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/Person",

"http://example.org/is_born_on": {

"@type": "http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema#date",

"@value": "1925-09-16"

},

"http://example.org/plays_instrument": {

"@id": "http://example.org/Guitar"

}

}

Serialized forms

The RDF statements in each of these examples is the same, but encoded or serialised via different content types - JSON-LD, RDF/XML or Turtle (and more). This provides more options for developing applications for users and consumers of this data. Some consumers implementing web browser applications may prefer the JSON-LD serialisation as there are compatible web front-end libraries to consume the data. Others may prefer the other content types (RDF/XML, Turtle, N-Triples) which may be supported by programming languages such as Java and Python.

Namespaces

The last thing to note about the above examples is the use of namespaces. Each namespace denotes a “vocabulary” which is a set of RDF terms. A local prefix can be associated with a namespace which allows a URI from that namespace to be aliased to a more compact “colonised” form -

e.g. foaf:Person == <http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/Person>.

There are many existing vocabularies and ontologies published by W3C, DCMI, the OBO foundation, OGC, and various other initiatives including the Australian Government through AGLDWG.

A selection that are recommended for re-use are listed in RDF vocabularies and ontologies that you can trust with the namespace prefixes that are conventionally used.

Use of properties and types from well-known vocabularies in your application enables greater data integration opportunities, and common tools to parse/render the data. For example, FOAF (or Friend-of-a-Friend) is a namespace with properties and types for describing people. It is used in the above example to express that B.B. King is a person. Use of FOAF allows that piece of data to be integrated with other data that use foaf:Person. This applies to other defined types and properties, e.g. namespaces include rdfs:, skos:, owl:, dc:, dcterms:.

Refer to Section 1 of the “Linked Data Example 1.ipynb” Jupyter Notebook example.

“Conneg” (Content-negotiation)

By format / media-type

The HTTP protocol allows content-negotiation via headers (as key-value pair values) which accompany the request. The Accept request HTTP header advertises which content types, expressed as MIME types, the client is able to understand. Using content negotiation, the server then selects one of the proposals, uses it and informs the client of its choice with the Content-Type response header. Browsers set adequate values for this header depending on the context where the request is done: when fetching a CSS stylesheet a different value is set for the request than when fetching an image, video or a script.

The Accept request-header field can be used to specify certain media types which are acceptable for the response. Accept headers can be used to indicate that the request is specifically limited to a small set of desired types, as in the case of a request for an in-line image.

The following example shows the Accept field that accompanies the HTTP request, i.e. For this HTTP request, I would like (to Accept) this response format (text/plain):

Accept: text/plain

Often browsers will have default Accept headers such as this:

text/html,application/xhtml+xml,application/xml;q=0.9,image/webp,image/apng,*/*;q=0.8

For Linked Data applications, these are generally the mime-types that are accomodated:

application/rdf+xml(RDF XML serialisation)text/turtle(Turtle serialisation)application/ld+json(JSON-LD serialisation)text/n3(N3 serialisation)application/n-triples(N-Triples serialisation)

Run through the Content negotiation by Media Type section in Tutorial on LD APIs Part 1.

By profile

TODO: Add more content on conneg by profile

See Content negotiation by profile

Run through the Content negotiation by Profile section in Tutorial on LD APIs Part 1.

Linked Data APIs

Linked Data relies on existing web standards and approaches - URIs, HTTP and content types and REST. However, other than that, there is currently is no standard patterns for delivering data resources on the web, i.e. middleware to publish Linked Data resources and APIs for making it easy for developing applications while adhering to Linked Data principles and approaches.

Linked Data APIs (LD-APIs) and implementation software enable the publication of data as Linked Data. The implementation code libraries provide an important bridge between the data and Linked Data consumers by implementing features. Features include Content Negotiation by media type (HTML vs. JSON-LD vs. Turtle vs. RDF/XML) and more recently, Content negotiation by profile, which allows users to query different views of the data.

Practice

This section outlines practical aspects of applying Linked Data APIs in implementations as well as examples deployed.

Code libraries

Code libraries for implementing Linked Data APIs are listed below:

| Library | URL | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| pyLDAPI | https://pypi.org/project/pyldapi/ | |

| ELDA | http://epimorphics.github.io/elda/current/index.html | |

| SKOSMOS | http://www.skosmos.org/ | |

| Linked Data Registry | http://ukgovld.github.io/ukgovldwg/guides/registry.html |

Implementations/instances

A list of Linked Data API implementations and instances are listed below with the LDAPI Library used included.

| Implementation | URL | LDAPI Library |

|---|---|---|

| Loc-I ASGS Dataset | https://asgsld.net/ | pyLDAPI |

| G-NAF Dataset | https://gnafld.net/ | pyLDAPI |

| Geoscience Australia Samples Registry | http://pid.geoscience.gov.au/sample/ | pyLDAPI |

| ARDC’s RVA | https://documentation.ardc.edu.au/display/DOC/Linked+Data+API | ELDA/SISSVoc |

| UNESCO Thesaurus | http://vocabularies.unesco.org/browser/thesaurus/en/ | SKOSMOS |

| AGROVOC (FAO) | http://aims.fao.org/vest-registry/vocabularies/agrovoc | SKOSMOS |

| Finnish Library vocabulary | http://finto.fi/en/ | SKOSMOS |

| Ordnance Survey Linked Data Platform | http://data.ordnancesurvey.co.uk/ | Linked Data Registry |

| Environment Registry | http://environment.data.gov.uk/registry/ | Linked Data Registry |

| WMO codes registry | http://codes.wmo.int/ | Linked Data Registry |

| CSIRO Linked Data Registry | http://registry.it.csiro.au/?_browse=true | Linked Data Registry |

Worked example using pyLDAPI

Run through Tutorial on LD APIs Part 2.